What was my grandfather’s profession? Why did my grandmother move to Vienna? Where did my ancestors come from? Is it true that my great-grandmother had nine children?

Questions like these often mark the beginning of a true passion – the passion for genealogy. When we talk with our parents, grandparents or other relatives we soon come to realize that oral history has its limits. Some of the stories passed on in the family don’t stand up to closer scrutiny. We need to do our own research if we want to answer these questions.

Up until the year 1938 and for all Austrian provinces except Burgenland, the religious communities performed those civil functions that are today within the responsibility of the state. The church registers on baptisms, marriages and deaths are therefore the main source of information for any research on genealogy. Digitization has made it possible that we can easily do research from far away, since the church registers of almost all Austrian dioceses are by now available online.

This page aims at giving answers to the many questions that everyone has at the beginning: How do I start with my research on genealogy? Where can I find the relevant information?

Step 1 – Collecting documents from parents and grandparents

Your own birth certificate as well as the documents of your parents are the first step in your genealogical research. The birth and marriage certificates of your parents also hold the names of your grandparents. Maybe your family still has your grandparents’ documents or a so-called “Ahnenpass”, a proof of ancestry from Nazi Germany. These records provide additional information for further research.

The number of ancestors doubles with each generation. Two parents, four grandparents, eight great-grandparents, and a few generations down it’s 64 fourth great-grandparents. It is important to start your research on a well-organized basis, otherwise it will be difficult to have an overview when the number of known ancestors is growing. The following template may be helpful for that purpose: Pedigree Chart

Later on you can enter the data into one of the many software programs that are available for genealogy.

In the template we are using here, enter your own name in the box at the bottom (number 1). You are the reference person, in genealogical terms the “subject”. Enter your father in box number 2, your mother in box number 3, and your respective grandparents in the boxes numbered 4 – 7. The number of each father is twice the number of his child; the number of each mother is the father’s number plus 1. This system is used to identify each ancestor by a unique number. In genealogical terms it is known as “Ahnentafel” or “genealogical numbering according to the Sosa-Stradonitz Method”.

When you have entered the names of all the persons you know, continue by adding the date and place of birth as well as the date and place of death for individuals, and the date and place of marriage for couples. Make sure to enter the individuals’ denominations which you will need for any research prior to 1939.

This template is using the standard genealogical symbols for births (*), marriages (oo) und deaths (+).

Step 2 – Visiting relatives

Your relatives may be a valuable source of information. They may have further documents of common grandparents or great-grandparents, or maybe they have already done some research into your common ancestors. Just start to talk about the family and you may learn about something you didn’t know before or get some valuable clues.

Older people sometimes remember names, events or details when you talk with them a second or third time. You should therefore take your time, ask specific questions (“Tell me about your grandparents. Who was the talker, your grandma or your grandpa?”). Let them talk freely about stories that may not be related to your search for ancestors. You never know where these stories will lead you.

Don’t forget to bring some writing material and a camera with you. Maybe you can also take along a laptop and a scanner – some people don’t like to lend out the documents and pictures in their possession.

The following form may help you take down the most important information in an organized way: Family Data Sheet

You might ask your relatives if they have any of the following:

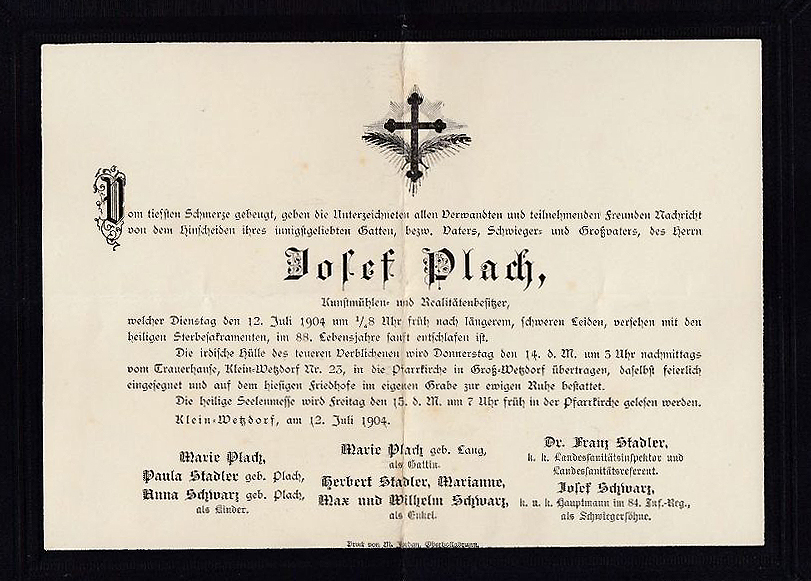

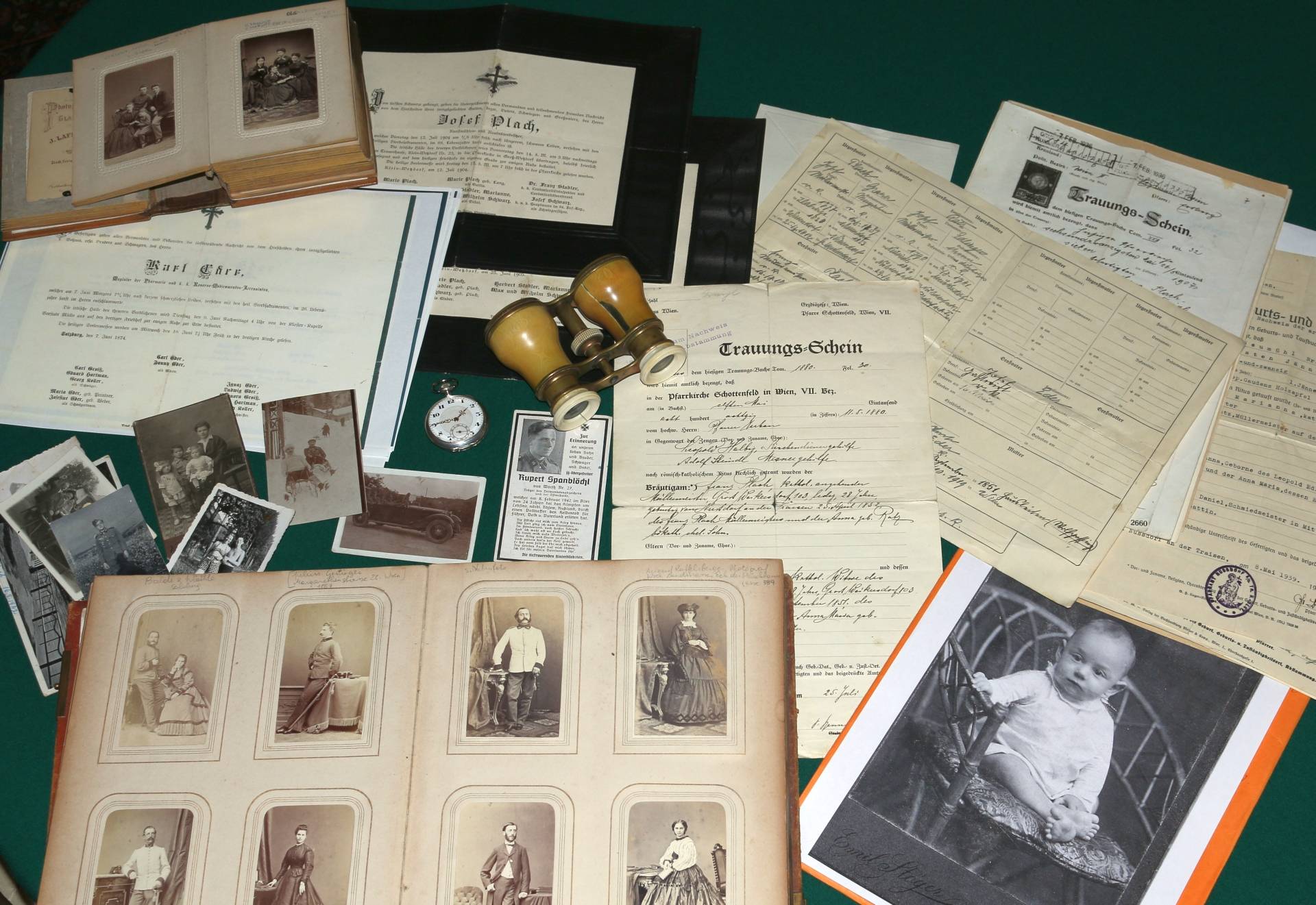

- Documents

- Pictures, letters or postcards

- Death notices, obituaries

- Diaries

- Etc.

By now you will probably have reached a point where it is important to note the exact source of each piece of information. Later on you may need to look the information up again.

Some examples:

- “Civil registry office of Stockerau, Birth certificate No. 123/1952, dated April 30, 1952“

- “Information given orally by Maria Huber, born February 22, 1922, in Stockerau“

When you receive oral information it is important to note the person’s birth date, as some names will come up several times.

Death notice (“Parte”) for Josef Plach, mill owner in Klein-Wetzdorf, Lower Austria. The relatives of the deceased are indicated with their names and degrees of relation.

You might also think about visiting the local cemetery together with your relatives. Older tombstones often hold a lot of information. Be careful about the inscriptions: Sometimes the baptism date is indicated instead of the birth date, or the date of the funeral instead of the date of death.

Take pictures of the family graves you have found, mark the date of your visit and transcribe the inscriptions which are often hard to read on a picture.

Tombstone of the Obenaus family, Döbling cemetery, 1190 Vienna, Hartaeckerstrasse 65, group 26, grave 7

Step 3 – Processing the available documents and information

Carefully take off any adhesive strips from the original documents. If you need to do some restorative work, make sure to use adhesive strips suitable for that purpose. Next, sort the pictures and documents by person.

Use naming conventions and an appropriate folder system for digital documents. With efficient sorting in mind, you might use the following naming conventions:

“Last name_First name_Event_Year_Month_Day_Place_Type of document“

For example:

- “Huber_Anton_Born_1828-12-21_Stockerau_Certificate of baptism“

- “Maier_Maria_Died_1946-09-13_WienStAWähring_Death certificate”

Use a soft pencil to label printed pictures on the back and sort them.

Once you have prepared your material, enter the information it contains into the two forms you have downloaded earlier.

Step 4 – Reading old scripts

When you are dealing with old documents you will encounter a script you may not be familiar with: Kurrent.

This is an old form of German-language handwriting that was in use up until the first part of the 20th century. Kurrent was forbidden in 1941 and replaced with the “Deutsche Normalschrift”.

In the beginning it may feel as if you were never going to be able to read this type of handwriting – but don’t give up. A few writing exercises down the road and you will experience your first success.

If you are unable to find a course where Kurrent is taught, take a look at the following links for online self-study:

- Start by printing a font sample like https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurrent#/media/File:Deutsche_Kurrentschrift.svg and learn the individual letters by copying them.

- Margarete Mücke’s website has an excellent guide to Kurrent http://www.kurrent-lernen-muecke.de/pdf/Schreiblehrgang%20Kurrentschrift%20%202016-english.pdf with explanations and reading exercises in several fonts.

Reading Kurrent script is a matter of practice. It’s important to be patient and not give up. You will soon have your first success if you keep this in mind.

If a certain entry is really hard to read the reason is probably not the script itself but the fact that the writer wrote it rather poorly. Some ideas on what to do: Ask someone with experience for help, attend a meeting of genealogists and ask there, or post your request for help in a Facebook group, a mailing list or a forum. Make the work of those who want to help you easier by including the link to the text as well as its exact source!

Here is more on Kurrent script: https://oefr.at/en/old-writings/

Step 5 – Finding further sources

By now you have already assembled a first family tree based on the information available in your family. Now you want to find more ancestors. For your research in Austria, two types of sources are available:

- “Standesämter” (civil registry offices)

- Parishes

In Austria, civil registry offices were only introduced on January 1, 1939. Before that, the religious denominations were responsible for properly recording births, marriages and deaths. For the province of Burgenland which was part of Hungary up until the year 1921, the year of change is 1895, since this was the year when civil registry offices were introduced in Hungary.

In a nutshell:

5.1 For births and deaths AFTER January 1, 1939 as well as marriages AFTER August 1, 1938, contact the respective Austrian civil office. For the province of Burgenland, civil offices are to be contacted for births, marriages and deaths AFTER October 1, 1895.

This office can either be the “Standesamt” or the “Standesamtsverband” of an individual community, or in the case of larger cities the “Standesamt” of the “Magistrat”. For details on the respective office, use the link below for a list of all Austrian communities and cities: https://www.help.gv.at/Portal.Node/hlpd/public/content/99/Seite.991385.htmllp/applikation-flow?execution=e1s7

If you are looking for documents in Vienna, contact the Municipal Department 26, “MA 26 – Datenschutz, Informationsrecht und Personenstand”. You can also order documents online: https://www.wien.gv.at/english/e-government/documents/order/documents.html

5.2 For births and deaths BEFORE January 1, 1939 as well as marriages BEFORE August 1, 1938, check the information on sources for religious denominations described in Step 6 of this page. For the province of Burgenland, the religious denomination is to be contacted for births, marriages and deaths BEFORE October 1, 1895.

5.3 Locked records

In accordance with the Austrian Civil Status Act, records are locked for a certain period of time depending on whether the record concerns a birth, a marriage or a death.

The following periods of time apply for records held in today’s Austria:

- Births: Records are locked for 100 years after the birth of a person, provided that the person is no longer alive.

- Marriage: Records are locked for 75 years after the marriage took place, provided that none of the partners is still alive.

- Deaths: Records are locked for 30 years after the death of the respective person.

Please note: These restrictions do not apply to direct ancestors or direct descendants. Since siblings and other relatives are neither direct ancestors nor direct descendants, the restrictions do apply to them.

Step 6 – Working with church registers

Once you have implemented all the information gained from family documents and the civil offices you proceed with the church registers.

These are the books kept by the religious denominations regarding baptisms, marriages and deaths. The earliest church registers usually start at the beginning of the 17th century, in some cases even in the 16th century.

In 1784, an Imperial Patent obliged the clergy to keep registers on baptisms/births, marriages and funerals/deaths. The Patent also provided for German as the language to be used, and for the information to be taken down in the form of tables. Church registers as of 1784 are known as “Altmatriken”.

6.1 Roman Catholic church registers

Click here for the links to the Roman Catholic church registers of today’s Austria and Czech Republic.

The easiest way to find the parish you need is by using the Gazetteer provided by Prof. Felix Gundacker on the GenTeam website (free of charge, registration required).

6.2 Protestant church registers (A.B. and H.B.)

Religious freedom was introduced in Austria in the year 1781 with the Patent of Toleration. In 1782, the Protestant Church was authorized to keep registers on baptisms, marriages and deaths. However, these books did not have power of proof. Therefore all births, marriages and deaths also had to be entered in the Roman Catholic registers.

Power of proof was only granted on November 20, 1829. And even then, duplicates had to be sent to the Roman Catholic parish so they would be registered there, too. In the same way, birth, marriage and death certificates were only legally valid if the Roman Catholic priest had signed them.

Full legal equality was granted on January 30, 1849. From then on, Protestants were only registered in the Roman Catholic books if the distance to the next Protestant church was too long.

As of 1829, duplicates of Protestant church registers were sent to the Consistory.

Click here for the links to the Protestant church registers that are available online.

6.3 Jewish registers

Jewish registers of the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde Wien 1784-1911 for Vienna, Ybbs – Amstetten, Zentralfriedhof burial records are available at:

6.4 Non-denominational marriages and marriages of partners belonging to different denominations

Beginning on May 25, 1868, non-denominational marriages had to be recorded in the form of “Aufgebotsbücher” (notices of intended marriage) and “Eheregister” (register of marriages) by the “Bezirkshauptmannschaft” (district offices) or, in larger cities, the “Magistrat”. They were called “Notzivilehe”, which roughly translates into “emergency civil marriage”. As of 1869, it was also possible for partners belonging to different Christian denominations to get married this way. A law issued on April 8, 1870 subsequently also dealt with the registration of non-denominational births and deaths.

An index of the civil marriages of Vienna, Graz and Salzburg beginning with the year 1870 is available on GenTeam under the headings [Vienna/Civil Marriages] as well as [Regional Austria/Civil Marriages Graz/Salzburg]. GenTeam also holds an index of civil births from Vienna [Vienna/Zivilgeburten].

6.5 Special cases

Hospitals: At the beginning of the 20th century, separate registers were introduced for hospitals to account for the large number of births and deaths. Before their introduction, births and deaths occurring at hospitals were entered in the parish to which the hospital belonged.

Military parish records: The military started to keep its own parish records in the year 1786. At small garrisons, however, the local priests usually also kept the registers for the military. Today the military parish records are kept at the Kriegsarchiv department of the Austrian State Archives. Some of them are already online: http://www.crarc.findbuch.net/php/main.php?ar_id=3738 , heading [ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv].

The province of Burgenland used to be a part of Hungary where civil registry offices were introduced in the year 1895. The legal power of the church records therefore ended at that time. The registers on baptisms, marriages and deaths are purely denominational records from then on.

Step 7 – Practical issues

Keep in mind that you always need to proceed systematically: You are starting with the earliest known date.

- If it is the date of a marriage, look up the marriage record in the respective church register. The entry will usually tell you the couple’s age, date and place of birth. Hopefully it also includes information on their parents, and maybe even on their grandparents. Enter all of this information into your family sheet and include the source where you have found it (e.g. Archive of the Diocese of St. Pölten, Parish Traismauer, Signature 02/17, Fol. 123).

- Next, look for the birth records of bride and groom in the baptism/birth registers of the respective parishes. These records again contain information on the parents. In the column at the very right titled “Anmerkungen” or similar, you may also find details on the parents’ marriage. Enter the relevant information together with the source and look for the marriage record of the parents.

- Repeat these steps: Marriage – birth – marriage of parents – birth of parents – marriage of grandparents – and so on.

Collecting random data on anyone with the name you are looking for won’t help with your research. Similarly, don’t skip years, decades or even centuries in the vain hope of finding aristocratic ancestors.

Tip 1: Finding places and records on individuals

You will frequently need to locate a particular place and its parish. The Gazetteer for Austria, the Czech Republic and Slovenia will prove to be a most valuable source of information. It is available at www.genteam.eu (free of charge, registration required).

The Gazetteer contains 72,000 places in Austria (with South Tyrol), the Czech Republic and Slovenia, with today’s and former names, the respective parishes (status: 1938) and previous parishes, the year the registers begin, the respective archive, the political district and the Crown Land. If the registers of the respective archive are online, the record is linked with the website.

www.mapire.eu is the perfect platform to use when it comes to finding a particular place. It offers access to the First (1763-1787), the Second (1806-1869) and the Third (1869-1887) Military Surveys of the former Habsburg monarchy, the plans (“Urmappen”) of the Franziszeische Cadastre for today’s Austria and parts of Hungary and Croatia, the Austrian Historical Town Atlas, and much more.

Tip 2: Spelling of last names

Keep in mind that there was no “correct” way in which to write last names. Priests and clerks wrote the names the way they heard them. Some examples:

- Baier, Bayer, Bayr, Baar, Bahr, …

- Plach: Blach, Blaich, …

- Pfaller: Pfaler, Pfahler, Pfoler, Pfohler, Pfoller, Gfaller, Phaller, Faller, Foller, …

Allow for variations like these when you search for a particular record.

Tip 3: Name indices on GenTeam

From the 19th century on, many parishes drew up indices to save time when they had to look up particular entries in their church registers. These indices are usually on the last pages of the respective book, but they may also be available as a separate index book for one or several church registers. Keep in mind that sorting is often phonetic: B and P as well as D and T are frequently entered under one heading. Phonetic sorting may also apply to the letters C, G and K.

The entries are usually sorted by the last name of the individuals; in the case of marriages it is usually only the groom’s name. The indices also contain a reference to the page (pag. = pagina) or the sheet (fol. = folio) of the register on which to find the entry.

Since many church registers have no index at all, genealogist Prof. Felix Gundacker has initiated Austria’s largest genealogical database collection, GenTeam. Besides the Gazetteer mentioned earlier and numerous indices of church records, GenTeam also contains many other important databases. Currently (April 2018) more than 41,400 researchers of genealogy and regional heritage as well as historians are using the databases which hold more than 18 million entries. Visit the site and register, you’ll see it’s worth it!

Tip 4: Genealogical dictionary

Time and again you will come across a term you simply do not know. In a situation like this the Genealogical Dictionary by Prof. Felix Gundacker is a valuable source for help. The dictionary was first published in the year 2000 and has now been extended to a total of 8,000 German/Latin as well as an additional 4,600 Czech terms. It covers the geographical area of those countries that used to belong to the Habsburg monarchy.

Felix Gundacker: Genealogisches Wörterbuch Deutsch, Latein und Tschechisch.

2nd, significantly extended edition, 12,600 terms, self-published, A5, 243 pages, cardboard cover, ISBN 978-3-902318-20-1, EUR 24.00 plus shipping & handling

Available at kontakt(at)FelixGundacker.at or https://www.felixgundacker.at/2020/01/16/neu-genealogisches-worterbuch/

Step 8 – Knowing who to ask

Multilingual mailing list

www.genlist.at, our multilingual mailing list with approximately 1.800 international subscribers

Forum Ahnenforschung Österreich

http://www.forum-ahnenforschung.eu

Facebook groups with a regional focus

Postings in English are welcome in all of our Facebook groups.

Vienna, currently more than 2,500 members

https://www.facebook.com/groups/Ahnenforschung.in.Wien

Lower Austria, currently more than 1,100 members

https://www.facebook.com/groups/Ahnenforschung.Niederoesterreich

Lower Austria as well as Upper Austria

https://www.facebook.com/groups/1645766715438402/

Upper Austria, currently more than 550 members

https://www.facebook.com/groups/Ahnenforschung.in.Oberoesterreich/

Salzburg

https://www.facebook.com/groups/Ahnenforschung.in.Salzburg

Styria, currently almost 400 members

https://www.facebook.com/groups/Ahnenforschung.in.der.Steiermark/

Burgenland, currently more than 550 members

https://www.facebook.com/groups/Ahnenforschung.Burgenland

Tyrol (territory of 1918)

https://www.facebook.com/groups/202068550438854/?ref=br_rs

Czech Republic, currently more than 1,500 members

https://www.facebook.com/groups/Ahnenforschung.in.Tschechien

Slovenia

https://www.facebook.com/groups/ahnenforschung.in.slowenien/

Hungary

https://www.facebook.com/groups/Ahnenforschung.in.Ungarn/

Genealogy and military history, currently more than 550 members

https://www.facebook.com/groups/1868300346780528/?ref=br_rs

or come to one of our monthly meetings, the GENEALOGENSTAMMTISCHE. The dates are published on the Events page.

Further tips are available on our Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/Portal.Ahnenforschung.Oesterreich/ and our WIKI (both in German).

Step 9 – Time to get started!

We wish you a lot of success in your research!

You must be logged in to post a comment.